What do sounds do? They make us feel what it means to be alive. In that sense, sound redefines ‘life’. It shapes the conditions through which life becomes perceptible. This realization became palpable to me last month at SOUND+PURPOSE: Inaugural Conference of the SOUND+ Network for Transdisciplinary Research in Sound, hosted by the Sound Environment Centre at Lund University. The conference arrived with the promise of artistic and intellectual exchange across disciplines. I went there with a simple, pragmatic intention: to present my work, share it with others, and receive feedback that might help sharpen it further. But as I look back on those two days, they feel less like an academic event and more like a musical composition; something akin to a Jimmy Page or Nikhil Banerjee piece. Page, with the gritty distortion of his guitar, and Banerjee, with his heart-bending jhaalaa (the fast, climactic section at the end of a raga performance) and soul-twisting meer (a smooth, continuous glide from one musical note to another), possess an uncanny ability to pull listeners into labyrinths of sensation and imagination. Slow, immersive, contemplative. Unpredictable, vulnerable, and untameable. Much like their iconic guitar and sitar solos, the conference, or rather, the confluence, stirred something that ordinary moments of life rarely do. Threaded through distinct motifs and overlapping melodies, the event facilitated an impromptu composition of multiple voices: artists, scholars, and practitioners, that somewhat felt like an unanticipated sonic intervention. It overwhelmed, unsettled, and compelled me to think, feel, and encounter the mundane through an arrhythmic sequence of vibrating tremors. I explain shortly why I use the phrase vibrating tremors.

Individual presentations, performances, listening-room sessions, and most importantly, the conversations and informal exchanges, all seemed to twist my knobs, like a radio. I tried to absorb as many signals as possible, searching for a frequency that might connect them all. That frequency became partly audible when I attended a performance by Sylvain Souklaye, a French-Caribbean live artist, sonic maker, and author based in Brooklyn, New York. Souklaye’s practice resists reductive framings of identity. He engages with rhizomatic entanglements of bodily vulnerability, ecological crisis, and political violence, as these emerge through interior histories and lived sensitivities.

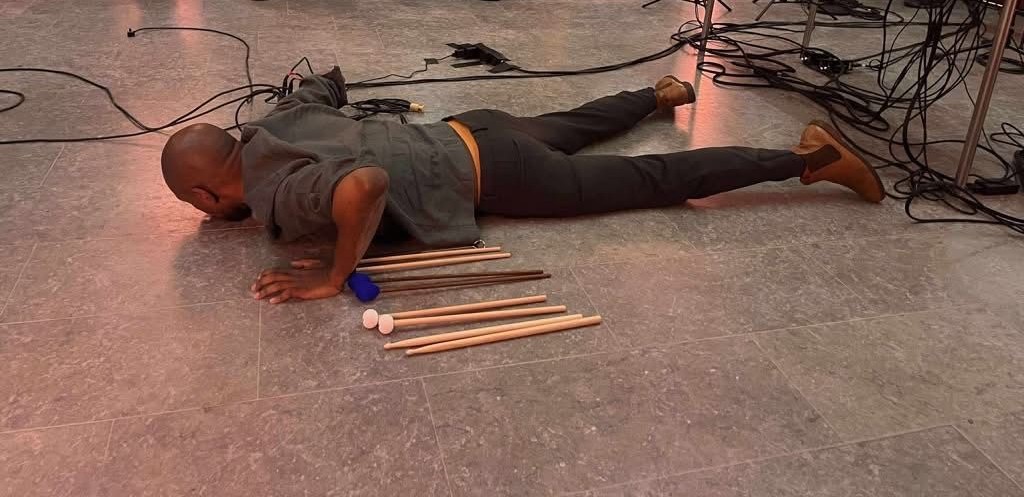

On November 20, Lund witnessed its first snowfall of the 2025 winter season. Residents and students documented the moment as the snow continued to fall into the evening, crystallising into a thick white blanket by the following morning. After a full day of panel presentations at the LUX building at Helgonavägen 3, it was early evening, somewhere between 17:30 and 18:00, when the city, covered in snow, gathered us once again. A red-and-black hue spilled across the floor. Souklaye lowered himself to the ground. Pin-drop silence. Lying flat before beginning to move, slowly, deliberately, his body pressed against the surface as he crawled. Over nearly an hour, the performance opened into a shifting landscape of sounds and movements. One by one, audience members were drawn in. Each of us contributed our own sounds and gradually entered an unstable, metamorphic pool of human-machinic sonorities. It began as a performer-centred act but gradually transitioned into a collective space, orchestrating a polyphony of bodies, machines, breath, and air, all vibrating together in conflict, convergence, and confusion. What stayed with me most was Souklaye’s inaugural gesture of intimacy with the ground. At one moment, he pressed his fingers to the floor and scratched its surface with his nails. The amplified sound felt nauseating. It was sharp, dry, abrasive. It scraped against my nerves and induced a sense of inexpressible discomfort. Within that discomfort, a question kept surfacing: Can the ground speak? Can it respond and communicate? Each time the surface was touched, it seemed to respond with a sonic gesture. If concrete matter could be reactive, responsive, and expressive, can it be considered inert at all? More questions crawled in. Do materials we routinely dismiss as non-living carry traces of life that exceed our habitual modes of sensing and knowing? Can ‘life’ be thought beyond our anthropomorphic conditioning? In simple words, is life exactly what we have been taught it is, or could it be otherwise?

Instead of articulating it through a syntactic order of language, the ground began to communicate through vibration. In Listen: A History of Our Ears (2008), French philosopher and musicologist Peter Szendy describes listening as a form of responsibility; it is a response-ability, an openness to answering what one hears. Souklaye’s performance pushed this idea further. We are accustomed to relating to the ground through our feet, through balance and movement. But what happens when we relate to it through our ears? Or, more precisely, through the entire body: skin, muscle, breath, and attention? Such forms of listening gesture toward another mode of being with the world, one that recognises communication not as exclusively ‘human’, but as distributed across vibrating bodies, substances, and materials.

Thoughtfully titled Intimacy: Sound as a Catalyst for Collective Vulnerability and Spatial Transformation, this act invited a recalibration of listening itself, toward attunement with the subtle, uneasy, and often overlooked conversations already taking place between bodies, machines, and the ground beneath us. In the next part of this Sound+Purpose blog series, I will reflect on more such performances, presentations, and exchanges that taught me a great deal about sound, vibrational epistemologies, and life.